Having paused for thought and consideration, and having taken the advice of my learned friends and colleagues in GHS, let’s review the story so far …

In August 1900, this old chap, Mark All, an out of work engineer, down on his uppers, took up a wager (with all sorts of strings attached) with Alfred Harmsworth that he could not walk 300,000 miles in 21 years. (Or so he said) – because when we (we’re on this case together, you understand) scratch the surface of this claim, it soon becomes apparent that both the duration of the challenge and the amount of the prize differs as time goes on. This leads me to be curious as to the actual facts of the matter.

Eventually, I suppose, I would like to get to the bottom of his claim, but not at the cost of spoiling what is a fantastic – in the true sense – tale. And anyway, ‘eventually’ – presently – is a long way off. Hopefully not the twenty-five years Mark All tramped from place to place, but we surely have sufficient time to emerge ourselves in his contemplation just now. How to go about this? Which is our best foot forward? What are the broad parameters? First, I think, and this will be the task for today, we need to find out something more about the man himself. What we need first of all is an identikit picture. So, back to the British Library I will go.

Here’s where we left off: at 10.00am on Tuesday 29 May 1906 Mark All had presented himself at the office of the SUSSEX EXPRESS, SURREY STANDARD & KENT MAIL in Lewes. Visits like this to the local newspaper were obviously part his modus operandi. They served not just to make a mark on the calendar as to the time and place of his whereabouts, but also, crucially, in exchange for a story that would make for a few interesting column inches, the journalists would pass the hat round and present the proceeds to the old man to send him on his way. Totally level and above board, therefore, according to the rules of the wager’s engagement. Incidentally, remember, at this date the ‘distance /duration’ ratio was “60,000 miles in seven years”. Here’s part of what the paper printed the following Saturday (2 June 1906). It gives us clue as to his character as well as his original motive:

“The old man’s story is decidedly interesting. He was born at Greenwich, and apprenticed at some engineering works that town, and worked at his trade regularly for many years, but after the Employer’s Liability Act [1880] was passed he found it difficult to earn a living, as masters were not at all keen having men who were getting on in years to work for them. Rather than go on the parish All, despite his seventy odd years, set out find work of some sort or another, and it was while was tramping from place to place that it occurred to him try and establish world’s record in walking, and prove the absurdity of the argument that a man is “done for” so far physical energy concerned. “It was not begging tour that I undertook. I made up my mind to work, and, as far possible, support myself and do what good I could others. In the course of my travels I have worked on various jobs, and what help I have received has been the free gifts of people who have met me on the road.”

Whilst there’s no specific mention of Harmsworth, the journalist was told that:

“It appears that some gentlemen who are interested in All’s great effort have promised him a substantial reward should he achieve the object has in view, and the aged pedestrian is hoping that by this time next year will be the happy possessor of £5OO or more.”

“Great effort”. Certainly, if you care to look up ‘Pedestrianism’, you’ll see there is a long tradition of the ‘sport’, and quite a few contenders, including Blackheath’s very own George Wilson back in the early nineteenth century See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Wilson_(racewalker) And they were matched by an equal number of (usually languid aristocratic) backers. But few, if any, went to the lengths of Mark All.

The same article goes on to tell that Mark All averaged 45 miles a day; that presently he was on his seventh circuit of the British Isles and that he had tramped through Europe too. It relates some of the adventures (and misadventures) he met with along the way. These few facts are corroborated in articles elsewhere along his way. Did Mark All, I wonder, have a route in mind, or was his destination wheresoever the road led him?

In the St Albans, where Mark All gave an interview in mid-January 1906, he expands on this question among matters. Described as an ‘old fellow … wearing a somewhat weather-beaten appearance, but nevertheless looking wonderfully sturdy and in good spirits’, the journalist questioned him as to how far he had walked up to the present, and Mark All, ‘after referring to a diary which he keeps with commendable method, said he had walked up to Wednesday morning 40,7410 miles, leaving him 12,590 miles to traverse to complete his task: “With this object in view,” continued Mark All, I am going to Dunstable and Northampton; then I shall make my way right up to John O’Groats, and then perhaps journey right through Ireland, North and South Wales and then back to London … Asked if there were any wager at stake, Mark All said that if he completed the journey he would get £500 from certain London sporting papers, who had also helped him when he completed 30,000 miles.’

In the same interview he told the journalist he that his specific motivation had been the engineers’ strike in London of 1897-98. There’s an excellent account given of it here by John Grigg, Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society:

“The employers”, he said, gave the men clearly to understand that they considered them unfit for work after 45 years of age.” His idea was to prove this idea a fallacy. Starting from Fleet Street, London, on August 6th, 1904, he said “I was 72 years and two months old when I started, having been born on June 11th, 1828 at Greenwich. I am an engineer by trade, and served my apprenticeship at Greenwich, working afterwards for thirty years for a firm in Westminster Bridge Road. At the time of the engineers strike in 1897-8, I was working for Messrs Thorneycroft at Chiswick.”

A few months later, at the end of December 1906, Mark All was in Bristol where we are given this rough sketch of him:

“An elderly gentleman, wearing a Union Jack, triangle shape, on the sleeve of his left arm and a medallion of a brindle dog suspended round his neck … whose bones rest in France, after his long trot of several thousand miles at the heels of Mark All, his master”.

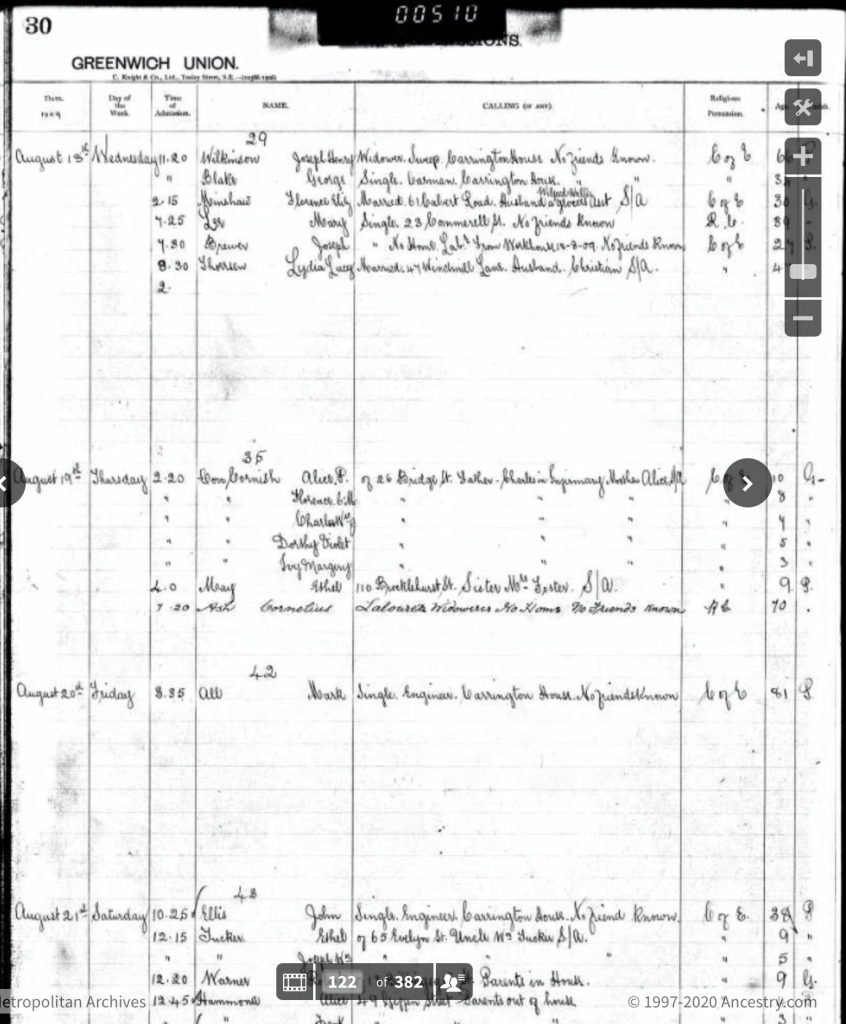

At least, therefore, the remark we find in the entry-book of Carrington House, the single-men’s hostel in Brookmills Road, Deptford where Mark All bedded down at end of play one August day in 1909 was not always true. No doubt, it was made for good administrative reasons, but still I find it shocking to read on the page these three words: “No friends known”.

How Mark All’s original challenge was carried on and carried out – how it transmuted into another, longer challenge, (and perhaps another) is a story for another day …

Evenin’ all.

Leave a Reply