A couple more clippings today which give a few snapshots of Mark All on his long trek. They date from the period between October 1905 to February 1907 when Mark All’s ‘first tramp’ (‘60,000 miles in seven years’) was underway and completed in good time. As you’ll learn, since August 1900 when he first set out from London, Mr All has travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles several times. He has been through Europe, too. He was intent on Russia as well but was unable to obtain a passport, ‘owing to the disturbed state of the country, and the many other matters demanding attention, the officials declined to be troubled with what they termed a fanatic.’

Here’s the first: October 7th, 1905, A RECORD WALKER AT UXBRIDGE. We meet up with old Mr All in the western outskirts of London, where he visited the offices of the Uxbridge and West Drayton Gazette to deliver an update on his progress thus far:

‘To walk 60,000 miles in all climes, and in all weathers, is by no manner of means an enviable task, but this is being done by Mark All, a septuagenarian mechanic, who has already covered over 30,000. The “Daily Graphic,” “Daily Mirror,” and “Sporting Life” [all three, Harmsworth publications, I think] made an offer that if he completed 60,000 miles in seven years, they would raise the sum of £500 for his benefit, and this offer Mark means to win. The “Daily Chronicle,” 12 months ago, exploited the, to many, inhuman theory that a working man is “too old at 40,” and it was to show the uncertainty of this statement, and as a practical protest against it, that Mark commenced his second walk of 30,000. He hopes to complete the 60,000 miles in December 1907. It is his usual custom to call at newspaper offices on his walk and report himself to the public through the medium of the Press, and, in accordance with this custom, he called in at the offices of this journal on Monday last week, having walked from Oxford that day in damp, muggy weather. Mark is of respectable appearance: his actual age is 77. Tall, grey haired, and with the ruddy glow of health upon his cheeks, Mark at once set to work in a cheery way to tell of his experiences and produced indisputable proofs of his statements, so that if one had any doubts as to the correctness of his self-imposed task, they were quickly set at rest. He started his great walk on August 6th, 1900, from Fleet Street, and is scheduled to finish in December, 1907, and he is now well ahead of the scheduled time. He has lately worked his passage to Boulogne, tram to Switzerland, and then on through Holland, and Belgium. He then retraced his steps and got into Spain, thence to Portugal, and, taking ship at Oporto, worked his passage back to Hull. From that port he walked on to Scotland and is now on his way front Holyhead to London.

“And where are you making for next?” we asked. “For Russia. I have not been able to go yet owing to the war, but I am hoping to make arrangements now that is over, and, if I succeed, I shall make right across the country to Siberia.”

This was said in such a casual way that it made one smile. Mark thinks no more of walking 40 miles than an Uxbridge man would think of walking four.

“You have had some rough experiences at times,” we remarked, after reading a newspaper cutting, which told that Mark, like the traveller of old who came from Jerusalem to Jericho, fell among thieves, who stripped him of his clothing and left him half dead in the road.

“Yes,” he replied, I have had some rough times, and had I known what I should have had to go through, l should not have taken on the other 3,000 miles. I have gone for days without food, but I have never yet seen the inside of a workhouse, and I never intend to until I am carried there.”

Mark is forbidden under the conditions governing the walk to solicit for alms, and he never does, but he is not debarred from accepting voluntary contributions to help him on his way, and there is one incident which Mark records with pardonable pride, and his eyes lighted up as he told the story. He was one day in the neighbourhood of Newmarket and was met by a party of gentlemen in a motor car, evidently having come from the races. Seeing his badge, and conditions of the walk, they stopped, and one of them asked him if he were the old man who was trying to walk 60,000 miles in seven years, and he said he was, and one of the party, to whom the others showed great deference, said: “Brave old veteran.” He told Mark to be sure to communicate with him when he had completed his task. “I will, your Majesty,” replied Mark, who had recognised the King. It is needless to say that Mark came away from that interview a richer and a happier man. He has walked 45,392 miles, and still has 14,608 to do. He wants to finish before December, 1907, if possible, but he has some bad country to do. He is the only walker recognised by the King.

“How did you get on in Germany,” was the next question put. “When I was in Germany,” he replied, I obtained employment for a short time at Bremen. They treated me very well there but didn’t forget when they found that I was an Englishman to chaff me about my country. Germany, they told me, was going ahead, and we should never recover the trade they had taken from us.”

“And did your own observations of German workmen tend to confirm that modest statement?”

Mark smiled. “Well, no, it didn’t,” he said. “Labour is cheap there. A first-class mechanic does not get more than 30s. per week; but the work is very inferior; I call it slop-work. Old as I am, I should not be afraid to back myself against the best man I saw out there.”

And by the way he said this one could not doubt the sincerity of it. “And France?” “Oh very well indeed; better, in fact, than I do in England, in spite of the difficulty in not knowing the language. I do not quite like the Swiss. They seem to me to be a very clannish sort of people.”

Mark’s luggage consists of a black handbag, which holds his tools and a few articles of clothing. The total weight is 28lbs. He has a book full of newspaper cuttings, recording his walk, and the names of the newspaper offices he has called at; also, a number of sketches. “I’m a rare draughtsman,” said the old man with a smile, as he carefully adjusted his spectacles, and produced pen and ink sketches, showing himself seated in a boat on the sea, with the inscription: ‘Mark All, on the Sea of Life.’

“I do this on the road,” he continued. “There’s my little ink bottle and pen. I make my diary up day by day, and I hope to have these sketches and remarks published in book form when I have completed my walk.”

“And it will prove interesting reading,” we ventured to remark.

“Well, yes: I’ve had a good deal of experience, and can use my tools now, old as I am. I’ve encountered much rough weather and gone days without food. It’s the wet weather that tries me most.” Mark has the satisfaction of knowing that, by walking 45,000 miles in five years, he has accomplished a feat which is absolutely unique, as the previous best performance was that of a German, and Mark records with pride the fact that he is the Englishman to whom it has been given to lower the Teutonic record.

From Uxbridge Mark All proceeded to Hammersmith, where he has friends.’

Where is that book of cuttings, those pen and ink sketches and diary now? Maybe, if they survived, they may still lie buried in an archive. What a prize they would be if they popped up on Ebay!

Mark All met the King more than once during his peregrinations. Eight months later, in mid-June 1906, when passing through St Albans (“for the seventh time”) ,he told the ‘Herts Advertiser’ that “[in] March of this year, when he was passing through Sandringham. “His Majesty sent one of his equerries to tell me he would like to speak to me,’’ said Mark All, and when I went, his Majesty said, “Well, you are still driving your pair of shanks, Mark?” I didn’t quite know what he meant, so I replied, “I am still endeavouring to complete my journey, your Majesty.” He said, “You haven’t much more to do now?” and I said, “A matter of 11,000 miles, your Majesty and he added “You will soon do that; that is nothing.” He told me if I lived to cover the 60,000 miles I was to be sure and communicate with him, and so I shall. His Majesty showed his interest in my attempt giving me five sovereigns and a good lunch.”

God bless Dirty Bertie! A square meal was a rare treat to Mark All as the same article goes on to describe:

‘Mark’s eyes glistened as he told of the good things placed before him; food enough for fifty people, served to him by waiters with powdered hair; and contrasted this with some of the sparse meals of which has had to partake by the wayside. His living is most precarious, and he asserted that often he would go without food for two three days for lack of funds. Producing a penny from his pocket when in the Herts Advertiser Office, he said, am pretty well on the rocks now; this is my last penny.” What steps you taken for procuring food when funds run out?” asked our representative?” “Then,” said Mark, “I go without. If have a copper or two I purchase raisins. I have often gone two hundred miles with a raisin in my mouth. Beer is no good, and I never drink water. I am not up to concert pitch to-day. though,” he added somewhat ruefully, for I celebrated my 78th birthday yesterday when passing through London, and I met friends there who would have me take drink or two, and it doesn’t do”.

Another gift of money came to him, we learn, through the beneficence of Joseph Chamberlain ‘the apostle of Tariff Reform’ who whilst speaking at Bedford during the general election earlier that year had started a subscription list among friends at his hotel, ‘and in the course of a few minutes had raised the substantial sum of £11 to help him on his way.’

“At what rate do you reckon to walk? was the next query put to Mark, who replied: “I can go six miles an hour, but don’t make it practice. Four-and-a-half or five miles is my rate.”

“Don’t you find the strain tolling upon you?” “No, I have had good health all the time; but I have been in considerable peril at times by strange characters. I have been robbed and stoned and left naked upon the wayside. I was treated worst in Germany, where I was stabbed. I think they were hostile to me there because I had beaten the previous record 40,000 miles walked by a German in five years. I have now beaten that record by about 11,750 miles.”

Interrogated as his plans for completion his task, the veteran pedestrian stated that he intended going from St. Albans on Tuesday to Luton and Bedford, on towards Liverpool, where he hopes to obtain passport enabling him to tramp through Russia and Siberia, returning to England by way of Ostend, completing his journeyings in London.

There was no doubt about his hopefulness in regard to the completion his task. “Given good health,” he said, cheerily, “I shall do 60,000 miles considerably under seven years. I am looking forward finishing in February next year.”

“How do you manage for boots?” asked our representative. “So far.” replied Mark, “I have worn out seven pairs, and these I have now are just beginning to go. I have to save up in order replace them.” [PS in the following September, when he was interviewed in the West Country, this tally had climbed to ‘42 pairs of boots … 32 shirts, seven suits of clothes and innumerable socks’!]

“Who mends your clothes?” “I do that myself. Here are needles and cotton, and here is my bag of buttons, and here,” said he, producing neatly-packed parcel from his overcoat pocket, are my soap and towel and brush.”

The series of small memorandum books, in which cuttings from newspapers all over the country referring to his travels, with numerous quotations and marginal notes, are kept by Mark All with great care, the volumes being arranged in chronological order and placed in cloth wallet. Observing that entries were made in ink, our representative inquired where the writing was usually done, and received the reply that it was, as a rule, accomplished at the roadside during a halt, Mark All, while speaking, producing from his waistcoat pocket a bottle of ink, and displaying pen which he carries in his tin spectacle case.

“…My handbag, in which I used to carry my belongings, wore out, so that I have now store away my things in my pockets.”

Undismayed by his precarious fortune, Mark All bade us cheery good-bye and passed on his way.’

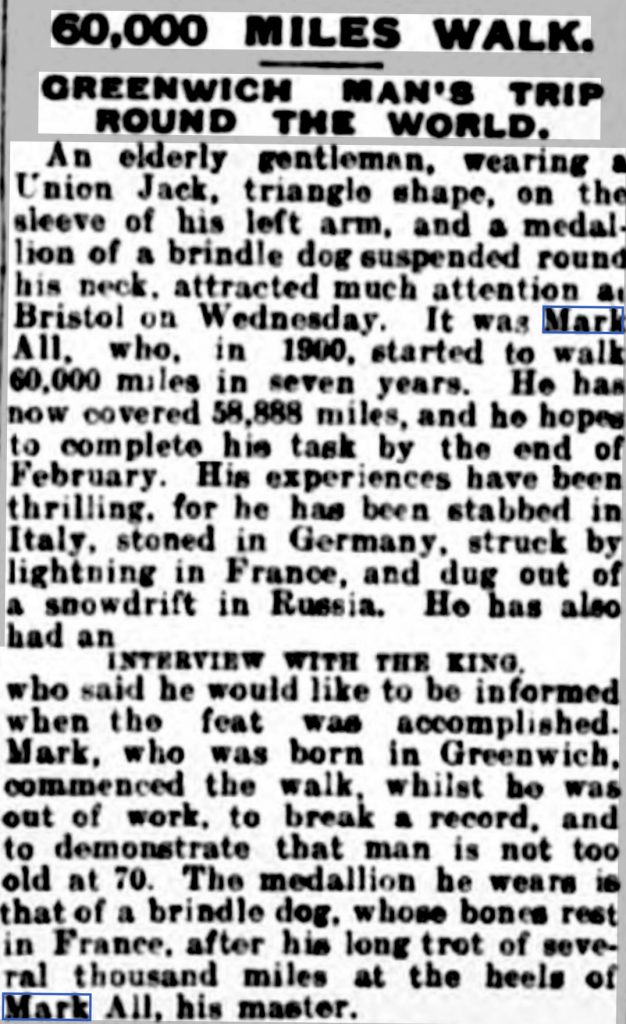

His dog [a brindle called, “Business”, as I have recently discovered] has died after accompanying him for 21,000 miles, now his bag has worn out! But Mark All was a man of courage and of staying power, having once set himself to a task he did not give it up. He meant to endure to the end of the journey! He was also blessed with a cheerful spirit. His fortitude must have been immense in order to confront the dangers he met with along the way: lost in snowdrifts several times, stoned in Germany, stabbed in Italy, struck by lightning near Marseilles, beaten, robbed, stripped naked and left for dead on Shap Fell. On the road from Belfast to Cork, he was forced to remove the Union Jack from his sleeve after the locals threatened to “do for him.” Just outside Bath he was met by two other tramps who threatened violence with a cut-throat razor, but they backed down when he ‘reminded them with a tap from a loaded stick [Harmsworth’s ‘stout walking stick’?] that he was not without arms.’ When asked about these experiences on one occasion, he replied “I believe there is no other man living who could have lived through the hardships I have endured. It is a mystery to me that I am alive.”

We can empathise then, with these otherwise mawkish lines he committed to his one of his notebooks and which were recited by him to the representative of the Wicklow Newsletter and County Advertiser in July 1906.

Across the foam far, far from home

The wanderer may steer;

But memory will never roam

From all he holds most dear.

A father’s and a mother’s love

Blooms when all else decays;

How prized and treasur’d are the hours

Of childhood’s happy days.

Mark All arrived in London in the first week of December 1906, having completed 58,888 miles of his attempt, but didn’t linger there long. By the end of the month he is reported to have been in Bristol. On the 8th of January 1907, he was in Hanley, Staffordshire (59.154 miles) where in the course of an interview he told how he had “spent Christmas Day on a heap of stones covered with snow on the roadside between Warminster and Bath. I had no food the whole day long, and as night approached, I had no shelter, and was so obliged to sleep in the snow.” But notwithstanding all his bitter experiences, the interview concluded, he had not allowed despair to overcome him.

On the 14th January he is reported to have been in Derby (59,225 miles) with ‘yet seven months before the completion of the time allotted to him tor his task.’ On the evening of the 22nd, he arrived at Bedford (59,451 miles), setting off again the following Monday heading for Barnett. Whilst there he told the papers that when he completed his task he stood to ‘win’ £1000; £500 from ‘the papers’ and £500 from a ‘number of certain gentlemen.’

The Nottingham Evening Post for 4th February reported (among other things) that The Grand Duchess Cyril of had given birth to daughter. Mr. Justice Ridley, at the Essex Assizes described the creed of the Peculiar People “horrible and ghastly” one. [That] although scarcely safe many are venturing on ice. [That] The Marquis of Salisbury will offer for sale 241 fine old Hatfield oaks at St. Valentine’s Day. [That] The Dominion Line has placed an order with Harland, Wolff, Belfast for a 14,000 tons twin screw steamer, for service between Liverpool and Canadian ports …

… AND finally, that Mr. Mark All, who is 79 … is expected to complete at Hyde Park Corner, on Sunday next, his walk of 60,000 miles, undertaken to demonstrate the fallacy the “too old by forty” theory.

Mark All duly completed his marathon walk on 14th February 1907, though I can find no particular report of this in the newspapers other than some published shortly afterwards in which he said to be looking forward to his interview with his old friend the King.

So, Mark All has passed ‘Go’, but the question is: did he ‘collect his £200’ – or was it £500, or even £1000?? And did he then hang up his boots? Not likely! Watch out for the next instalment in the long-walking saga of Mark All, “Ped”.

With deeper research, you will discover that Mark All was one of the many “around the world” walker frauds of the era. He lived mostly in workhouses as records show and then would pop out, visit a newspaper and tell his unbelievable stories. He also was likely 20-30 years younger. Most of these frauds were trekking (taking trains) across America at this time, but Mark All was a unique British fraud.