22 MARCH 2023. Following our (traditionally brief) AGM this evening, ANTHONY CROSS will give as this year’s President’s Address, ‘THE HORRIBLE AFFAIR: The Bomb in Greenwich Park, February 1894’.

The bomb that exploded in Greenwich Park in February 1894, killing the perpetrator, lies at the heart of Joseph Conrad’s novel ‘The Secret Agent’ (1907). Drawing on various contemporary sources, Anthony seeks to reveal the facts that Conrad later wove into fiction. In fact, the real bomber died without uttering a word of explanation as to his motive. Anthony will also explore some of the theories that might throw light on this mysterious incident.

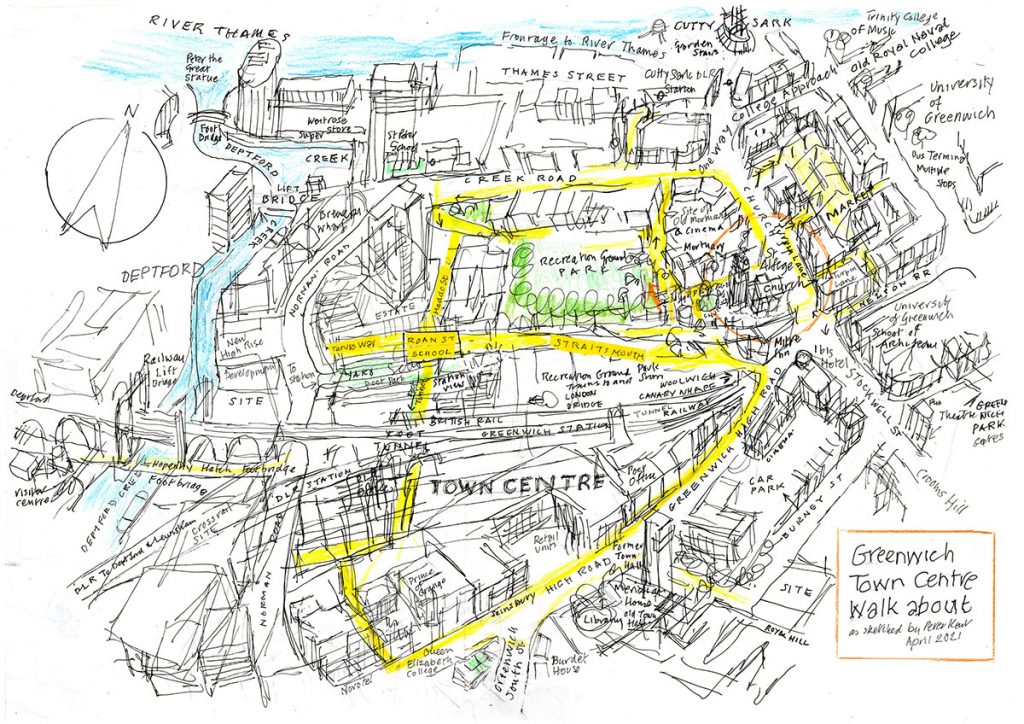

The meeting is held at James Wolfe School, Royal Hill Campus, Greenwich SE10 8RZ. Doors open at 7.15. Our AGM will commence at 7.30; the talk starts at approximately 8.00, and concludes at 9.00pm. We welcome non-members, from whom we invite a donation of £3 for each meeting.

The venue is well served by public transport. Bus routes 177, 180, 199 and 386 run along Greenwich High Road (at the bottom of Royal Hill). Bus routes 129, 188 and 286 serve nearby Greenwich town centre, and Greenwich Mainline Railway Station and Greenwich DLR are a short walk away.

There is free car parking after 6.30pm in the Burney Street car park (behind Greenwich Picturehouse).