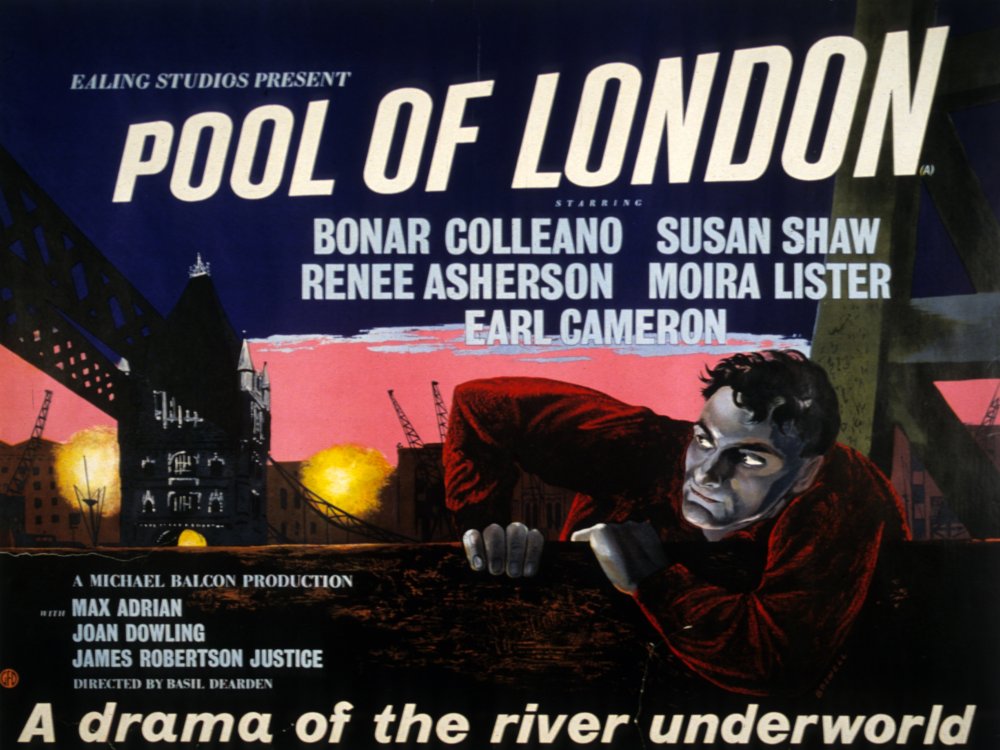

The action of Pool of London, Ealing Studios’ great film noir released seventy years ago this week, takes place over a London weekend. “The Dunbar out of Rotterdam bound for the Pool” passes through Tower Bridge on a Friday afternoon and the events that follow revolve around merchant seaman Dan (Bonar Colleano) and his Jamaican shipmate Johnny (Earl Cameron), the genuine affection of the friendship between them is established from the outset. Petty smuggling swiftly escalates to a diamond robbery and is played out against a background of real locations that give the film its authenticity and subsequent importance as a record of a lost London. This continued the highly successful approach Ealing established with Hue and Cry (1947), the definitive cinematic representation of bombed London, and followed with It Always Rains On Sunday (1947), Passport To Pimlico (1949) and The Blue Lamp (1950).

As Johnny unwittingly becomes embroiled in Dan’s misadventure, he experiences racism along the way but in each case these encounters serve to illustrate the ignorance and ugliness of the perpetrators: the hostile theatre Commissionaire (Laurence Naismith); the parasitic denizens of an all-night drinking dive, and Dan’s fair-weather girlfriend Maisie, a highly polished performance of brassy self-centredness by Moira Lister. Maisie’s venomous relationship with her younger sister (Joan Dowling) transcends sibling rivalry into undiluted hostility. When Maisie trips over her sister’s discarded footwear her complaint “Why don’t you put your shoes away? I nearly fell.” is met with the lightning riposte “Won’t be the first time!” In direct contrast is Sally (Renée Asherson) the wistful secretary at the Steamship Office, unlucky in love, who provides the film with its moral compass.

The early scenes on shore depicting the stage act of Vernon the Gentleman Acrobat (the incomparable Max Adrian) were filmed at the Queen’s Theatre in Poplar High Street. Millicent Rose provides a vivid record of a real performance at this theatre in The East End of London (The Cresset Press, 1951) observing that the aisles were strewn with peanut shells for “it is a long-established custom to crack and eat peanuts throughout the performance, and coming to the second house on a Saturday night, one finds the circle already deep in husks.”

Johnny strikes up a friendship with Pat (Susan Shaw) the cashier at the theatre box office, two lonely people thrown together by chance. Pat appears to be the least complicated and happiest of the female characters and her role is pivotal to the film’s significance as theirs is the first inter-racial relationship to be depicted in a British film. She and Johnny are undoubtedly the most attractive people in the film, providing the focus of its warmth and humanity and offering a ray of hope in the humdrum drabness. After an evening at the dance hall they spend Sunday sightseeing. Initially at the Stone Gallery at St Paul’s Cathedral, placing them in the City at the time of the robbery: “Look! Isn’t that a man climbing on that roof?” Afterwards they take the boat to Greenwich and we see them in the cavernous wonder that was the National Maritime Museum’s lost, lamented Neptune Hall (demolished 1996) providing an exhilarating reminder of what a proper museum once looked like. This cabinet of nautical curiosities is crammed with glass cases, ship models and binnacles and the location is deliberate chosen to reveal Johnny as a romantic philosopher, steeped in the lore and traditions of the sea, emphasised by a close-up of the towering baroque magnificence of the figurehead Ajax (1809). Passing through the colonnades of The Queen’s House, with the Naval College behind them, they walk up to the Observatory. The domed onion roof of the Great Equatorial Building is seen as a bare iron skeleton as its papier maché covering was destroyed when a V1 flying bomb fell on Greenwich Park in 1944. Here, with General Wolfe behind them, they muse on the mysteries of longitude and latitude.

“The Greenwich Meridian, but what does it mean?” Pat asks.

“It means that everything starts from here, goes right round the world and comes back here.” Johnny replies, reflecting: “You know, when you’re at the wheel of a ship at night far out at sea and nothing else to do, you think about a lot of things you don’t understand. You wonder why one man is born white and another isn’t. And how about God himself? What colour is he? And the stars seem so close and the world so small in comparison with all the other worlds above you, it doesn’t seem to matter much how you are born.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“It does you know. Maybe one day it won’t any more, but it still does.”

These were powerful words in 1951 and Earl Cameron’s performance had a profound effect on the distinguished film critic C.A. Lejeune, whose review of the film appeared in The Observer on 26 February 1951: “One thing comes shining out of Pool of London and that is the performance of Earl Cameron… he makes full use of every glancing minute… I can say with truth that Mr Cameron’s touching performance remains for me the best memory of Pool of London, and left me with deeper thoughts about the colour problem than I have ever had before.”

The authenticity of Johnny’s character can be ascribed to the fact that Earl Cameron was once a merchant seaman himself. Born in Bermuda in 1917, he arrived in London in 1939 experiencing racism whilst attempting to find a job (doors were slammed in his face), until he was eventually engaged as a dishwasher at an hotel, before he found himself on stage, at an afternoon’s notice, in the musical comedy Chu Chin Chow in 1941. Although not a trained actor he worked in the theatre throughout the forties. During this time he was proud to have had the privilege of being taught diction and voice training by Amanda Ira Aldridge (1866-1956), the daughter of the celebrated pioneering African American Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge (1807-1867) who achieved great success on the nineteenth century London stage. Cameron joked “that some of the colour might have rubbed off a little bit on me”. Pool of London was his film debut and Cameron secured the part after telephoning Ealing Studios to enquire about the possibility of a role in their forthcoming feature Where No Vultures Fly. Instead he was immediately invited to an interview with the director Basil Dearden at which Cameron lied about his age, stating himself to be 26 when he was actually 32, suggesting his moustache made him look older. Dearden was impressed by what he saw, although it took Cameron three screen tests before he was able to tone down the loudness of his declamatory theatrical delivery to suit the more intimate medium of film. Once this was mastered, he proved himself to be a natural film actor and the performance he gives as Johnny is one of great sensitivity.

Pool of London was not Ealing’s first exploration into the issues of race in Britain: The Proud Valley (1940) made a decade earlier is an extraordinary film with a strong political message and a powerful performance by Paul Robeson as a sailor in a Welsh mining village who motivates his community in the wake of a pit disaster. Robeson regarded this as his favourite film and retained a strong bond with the Welsh miners for the rest of his life. Both films are notable as presenting un-stereotypical depictions of men of colour who are accepted within their communities. Cameron stated that generally speaking he had not experienced prejudice whilst working in theatre and film industry in Britain and although the environment at Ealing Studios was entirely white he was treated with courtesy and kindness. He eschewed a career in Hollywood, a place he believed to be far more overtly racist and which he thought would have destroyed him. Cameron received favourable notices for Pool of London, and his roles in subsequent films, including The Heart Within (1957), Sapphire (1959) and Flame in The Streets (1961), form a significant body of work as pioneering cinematic depictions of the experiences of black people in Britain and the problems they endured. Earl Cameron continued working well into his nineties and died in 2020 aged 102. The heartfelt and sincere tributes paid to him recognised his unique position and the importance of his role in the advancement of performers of colour.

The idea for Pool of London came from John Eldridge and the scriptwriter originally assigned to the film was Ealing stalwart T.E.B. Clarke. The film’s original premise concerned the theft of gold bullion from the Bank of England and Clarke hit upon the idea of turning the gold bars into Eiffel Tower paperweights to enable them to be smuggled out of London incognito. Clarke was amused by the comedic possibilities and worked the idea into a three-page outline that radically changed the nature of the film. When he revealed this unexpected development, asking whether the river aspect of the plot could be dropped, the head of Ealing Studios Sir Michael Balcon erupted in fury. He took Clarke off the project, replacing him with a different writer Jack Whittingham, but allowed him to develop his idea further with the director Charles Crichton. The result, of course, was The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) one of Ealing’s most celebrated comedies for which Clarke received an Oscar for the screenplay. Alfie Bass is the link between the two films, appearing as a member of the gang of criminals in both.

James Robertson Justice plays Chief Engine Room Officer Trotter, resolutely staying aboard the Dunbar by retreating to the safety and seclusion of his cabin in company with three bottles of brandy and The Oxford Book of English Verse. He proffers this damning critique of the Capital he avoids: “You wonder perhaps why I never set foot in this accursed city. Behold from afar it gleams like a jewel, but walk within the shadow of its walls and what do you find? Filth, squalor, misery.”

Despite his denouncement, and notwithstanding the desperation, loneliness and need for self-preservation of the characters represented, London is not as squalid as he supposes. In fact, what is striking is, despite the post war deprivations in the aftermath of the Blitz, just how clean the city is, and it certainly appears to be far better kept than it is today. The water cart dousing the pavements of Tower Bridge at midnight is a visible manifestation of metropolitan ablutions; elsewhere the play of light on the wet cobbles and the light catching the kerbstones give the streets the impression of having been varnished. The gleaming quality extends to the frontage of a pub, the glossy ceiling of the café when the job is planned and the sparkling white tiles in the Rotherhithe Tunnel.

Great credit for the stunning visual appearance of the film must go to its director of photography Gordon Dines who achieved a lustrous luminosity. The documentary technique is employed to great effect, exploiting the aesthetic qualities of cranes and derricks, sails and ropes, barges and lighters and the ever constant movement of the play of the water with its waves, wakes and washes, emphasising that the River itself is to be the true star of the film: the working river, flanked by wharves and warehouses, with Tower Bridge looming large overall. Many scenes are shot in near silhouette and the dramatic shadows cast by ropes and ironwork bear favourable comparison with the photographs of Bill Brandt.

Pool of London was made in 1950 and released in February 1951 yet there is no inkling of the impending Festival of Britain “improvements”. The architectural fabric shown here essentially remains a nineteenth century streetscape, the Victorian survival. For Ealing Studios appreciated (what most politicians and town planners have signally failed to grasp) that London was a vernacular city and authentically represented it as such on celluloid, realising that the shops, pubs, cafes, theatres and back streets of terraced houses, in addition to more set piece locations such as Shad Thames, Tooley Street, and Leadenhall and Borough Markets, were far more representative of its true character and recognisable to its audience who appreciated their familiarity.

For the rooms inside these buildings, the film’s art director Jim Morahan instinctively understood the vernacular interior and his settings are infused with an eye for detail and richness that add great interest and depth, whether ship’s cabin, theatre dressing room or public bar. Nowhere is his artistry more apparent than in Maisie’s kitchen, replete with cast iron range and gas stove, with its peeling wallpaper, washing drying on the airer, milk bottles standing on the dresser, gaudy vases on the mantelpiece and proliferation of crockery and domestic detritus. This is just as it should be, for after all, Ealing invented kitchen sink drama one rainy Sunday in Bethnal Green in 1947.

© Horatio Blood 2021

The Royal Clarence Music Hall took its name from its location in Clarence Street (now renamed College Approach) commemorating the Duke of Clarence, subsequently King William IV. The architect was Joseph Kay, whose 1830s remodelling of central Greenwich is a masterpiece of Regency town planning. Kay’s original scheme for the northern entrance to Greenwich Market was a single storey portico with a pediment above. This was subsequently altered and extended to first floor level in order to accommodate a large room that was first licensed for performances in 1839.

The Royal Clarence Music Hall took its name from its location in Clarence Street (now renamed College Approach) commemorating the Duke of Clarence, subsequently King William IV. The architect was Joseph Kay, whose 1830s remodelling of central Greenwich is a masterpiece of Regency town planning. Kay’s original scheme for the northern entrance to Greenwich Market was a single storey portico with a pediment above. This was subsequently altered and extended to first floor level in order to accommodate a large room that was first licensed for performances in 1839.